The microbiota-that is, the microbial community found in the intestinal tract, formerly known as ‘bacterial flora’-has a crucial influence on human health, as numerous scientific studies have shown in recent years. The Covid-19 emergence has turned the spotlight on its role in, among others, the efficiency of the immune system. And it is also therefore that we are finally beginning to consider the role of individual foods-but more importantly, of different diets-on the microbiome and many aspects of health. A brief scientific review.

Microbiome, second brain and balance

The balance of the gut, in modern meaning, is associated not only with the function of the organ but especially with the high biodiversity and balance of the microbial community that populates it. This in fact interacts with the ‘second brain,’ a the dense network of neurons (>100 million) present in the intestinal tract.

The second brain in turn, communicates interactively with the autonomic nervous system through a bidirectional axis(gut-brain axis). And this is how a number of functions, starting with metabolic and immune functions, are modulated. With influence on blood pressure and cardiovascular system, energy balance and blood sugar, inflammation, and cognitive abilities.

Biodiversity and (great) variability of the microbial stock, as seen, are transmitted on matriarchal lines. After all, epigenetic programming in the fetus is influenced by a number of factors-dietary, environmental, psychological-that may intervene in the maternal microbiota. And so, after birth, on the condition of the host organism. (1)

Microbiota and nutrition

Nutrition is recognized as a primary influencing factor on the composition and modulation of the microbiota. Scientific research highlights several important aspects:

– The balance in energy, nutrient and micronutrient intakes,

– The quality of carbohydrates and fats, in particular,

– The essential role of fiber, prebiotics and probiotics, (2)

– the value of organic products and the risks conversely associated with exposure to environmental pollutants. Including pesticides and other agrotoxics still used in conventional agriculture.

24-48 hours is sufficient to alter the microbial ecology. (5) Which is first and foremost undermined by junk food (HFSS, High in Fats, Sugar and Sodium), which can send the immune system into a tailspin.

Carbohydrates, fats, fiber

Carbohydrates should express 45-60% of the energy intake in the diet, as suggested by the Italian Society of Human Nutrition (SINU). With marked favoring of starchy sources, due consideration of fruits and vegetables, minimization of simple sugars.

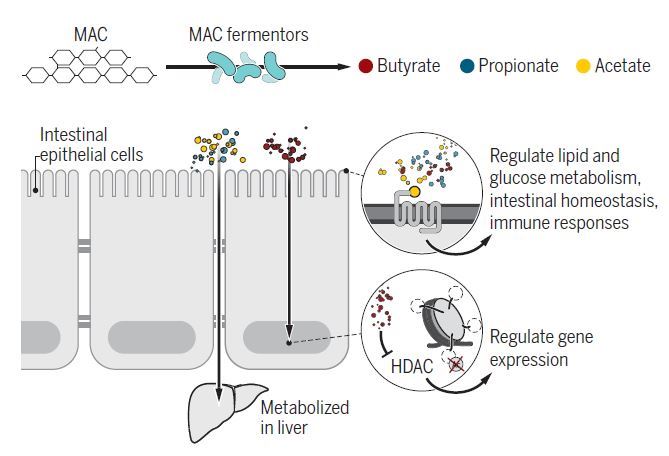

MACs, Microbiota-Accessible Carbohydrates, a diverse group of oligo- and polysaccharides, provide primary energy for gut bacteria. (3) Adequate intake of MACs–naturally contained in grains, legumes, vegetables, and fruits–thus enables maintenance of good microbial variability, with positive effects on health status. (4)

Dietary fibers-which include some prebiotics-are themselves indigestible polysaccharides, which pass the digestive tract to go to feed the intestinal microbiota itself. A diet rich in fiber has thus demonstrated the ability to stimulate the production of mucus that protects the walls of the intestine from pathogenic bacteria. And it is indeed associated with longevity and quality of life. (5)

Fig.1. Effect of MAC and its derivatives on the organism (Gentile et al., 2018)

In turn, fats can significantly influence the composition of the microbiota. Thus, high intakes of saturated fatty acids cause metabolic disturbances manifesting in inflammation of adipose tissues and increased insulin resistance and appears to reduce species variability. Omega 3, conversely, stimulates various favorable reactions on the immune system as well. (6)

What diet for the microbiota?

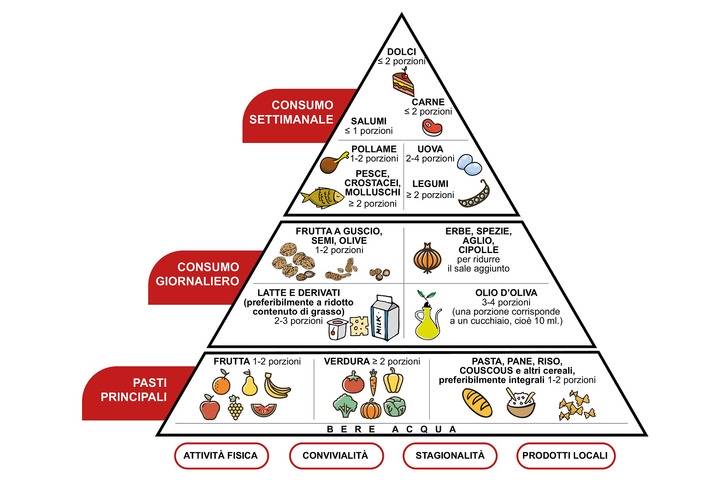

Mediterranean diet. The queen of diets on the Western quadrant is characterized by regular consumption of real ‘health ingredients’ that also have favorable impact on the microbiota. Such as extra virgin olive oil, various plant matrices rich in polyphenols, and oily fish. Adherence to this dietary pattern in turn has been associated with the development of beneficial microbial flora and the reduction of harmful microbial flora. (7)

Ketogenic diet. Reduced carbohydrate intake leads to metabolization of reserve fats, resulting in the formation of ketones (hence the name). A cohort study, moreover, showed how this diet-despite some observed benefits on weight loss-produces negative effects on microbial composition and gut health. (8)

Vegetarian/vegan diet. Veg diets have the advantage of high fiber and MAC intakes. In addition to phytochemicals, a category that includes polyphenols contained in plants. (9) Nevertheless, a study conducted by Italian and Swiss researchers found no major differences, at the microbiota level, in vegetarian, vegan and omnivore consumers. (10) This ‘is probably due to their common nutrient rather than food intake, e.g., high fat content and low protein and carbohydrate intake.’

Paleolithic diet. It replicates the dietary conditions of pre-agricultural societies, taking in a lot of protein and few carbohydrates, mainly due to the absence of grains and legumes. In one hunter tribe, the Hazda, this type of diet has shown important benefits, but there is a need to consider the intake of MAC-rich vegetables, which are often lacking in Western diets. (11)

Microbiota-mediated diet. Increasing attention to the positive relationship between health and microbial flora has stimulated the development of new diets, which often lack scientific evidence, however. Among the best known is the SCD(Specific Carbohydrate Diet), which restricts complex carbohydrates and refined sugars. (12) And the GAPS(GutAnd Psycology Syndrome) diet, which calls for the consumption of ‘only foods beneficial to the gut‘ and has, however, been the subject of controversy because of the way it is conducted. (13)

Fig. 2. The food pyramid, representative of the Mediterranean diet.

Research Horizons

Correlations between diet, microbiota symbiosis and health represent research horizons of great interest for the prevention of numerous diseases, including serious ones. Taking into account both strong genetic variability and epigenetics. A public-private synergy research project, theAmerican Gut Project, has been initiated in California with the goal of studying the microbial flora of the U.S. population using a citizen science approach, that is, offering voluntary contributions and participation by individual citizens. (14)

A major cohort study-conducted on nearly 50 thousand meals from a sample of 800 participants-showed the relationships between microbial variability and postprandial glycemic reactions. Setting the stage for the development of individualized diets aimed at lowering the glycemic curve in individuals at risk for diabetes. (15)

Research could also come to be directed, through randomized clinical trials, on correlations between the consumption of individual foods or their categories and microbiota health. In the wake of early studies conducted on some key ingredients of the Mediterranean diet, as well as on organic products, which could be extended to other foods, traditional and innovative.

The roles of ancient grains, cereals and legumes, hemp-but also algae and microalgae-on the microbiome and health could also be reevaluated from this perspective. So are animal products, to be considered as well in antibiotics-free and environmentally friendly versions (e.g., milk hay).

Diet and health, the outlook

The microbiome revealed high plasticity, which depends on environmental factors as well as the diet followed and individual food intake. This plasticity implies, on the one hand, the possibility of corrective dietary interventions with favorable impact on health. On the other hand, inattention to these aspects can quickly lead to dysbiosis conditions.

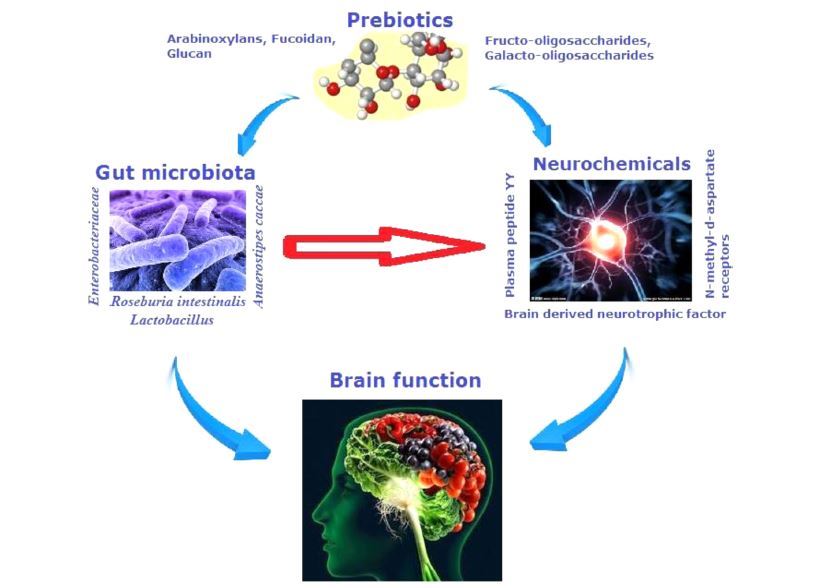

Fig. 3. Role of probiotics on the microbiota and nervous system (Liu et al., 2015)

Moreover, the variability increases sharply with advancing age. (16) Indeed, it has been shown how conditions of gut dysbiosis can reduce life expectancy and influence aging. Also with regard to chronic-degenerative and nervous system diseases. (17) Delving deeper into research on these issues can therefore enable the development of new prevention strategies of potential relevance to public health management.

Dario Dongo and Andrea Adelmo Della Penna

Notes

(1) Goldsmith et al. (2014). The role of diet on intestinal microbiota metabolism: downstream impacts on host immune function and health, and therapeutic implications. J Gastroenterol . 49:785-98, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00535-014-0953-z

(2) Sonnenburg et al. (2016). Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 535:56-64, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature18846

(3) Sonnenburg et al. (2016). Diet-induced extinction in the gut microbiota compounds over generations. Nature 529(7585):212-215, doi:10.1038/nature16504

(4) Maier et al. (2017). Impact of dietary resistant starch on the human gut microbiome, metaproteome, and metabolone. American Society for Microbiology 8(5):e01343-17, doi:10.1128/mBio.01343-17

(5) Holscher (2017). Dietary fiber and prebiotics and the gastrointestinal microbiota. Gut Microbes 8(2):172-184, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2017.1290756

(6) Gentile et al. (2018). The gut microbiota at the intersection of diet and human health. Science 362:776-780, doi:10.1126/science.aau5812

(7) Garcia-Mantrana et al. (2018). Shifts on gut microbiota associated with Mediterranean Diet adherence and specific dietary intakes on general adult population. Front. Microbiol. 9:890, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00890

(8) Tagliabue et al. (2016). Short-term impact of a classical ketogenic diet on gut microbiota in GLUT1 deficiency syndrome: a 3-month prospective observational study. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 17:33-37, doi: 10.1016/j.clnesp.2016.11.003

(9) Van Duynhoven et al. (2011). Metabolic fate of polyphenols in the human superorganism. PNAS 108(1):4531-4538, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1000098107

(10) Losasso et al. (2018). Assessing the influence of vegan, vegetarian and omnivore oriented westernized dietary styles on human gut microbiota: a cross sectional study. Front. Microbiol. 9:317, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00317

(11) Smits et al. (2017). Seasonal cycling in the gut microbiome of the Hazda hunter-gatherers of Tanzania. Science 357(6353):802-806, doi:10.1126/science.aan4834

(12) Cohen et al. (2014) Clinical and mucosal improvement with specific carbohydrate diet in pediatric Crohn’s disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 59(4):516-21, doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000000449

(13) Lawrence et al. (2017). Microbiome restoration diet improves digestion, cognition ad physical and emotional wellbeing. PLOS ONE 13(3):e0194851, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179017

(14) American Gut Project, http://americangut.org/

(15) Zeevi et al. (2015). Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell 163:1079-1094, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.001

(16) Kim et al. (2018) The gut microbiota and healthy aging . Gerontology 64(6):513-520, doi:10.1159/000490615

(17) Rinninella et al. (2019). Food components and dietary habits: keys for a healthy gut microbiota composition. Nutrients 11:2393, doi:10.3390/nu11102393