Trichinellosis, a disease caused by infestation of parasites belonging to the genus Trichinella, has now become sporadic due to the ubiquity of official public controls and the increased attention to avoiding the consumption of raw or undercooked meat of equine, swine and wild boar species.

It is one of the zoonoses under surveillance in all member countries. The most affected countries in 2018 were Bulgaria and Romania, which reported 45 and 25 cases of human trichenellosis, compared to only two cases reported by Italy(EFSA, ECDC, 2019).

Trichinella, the invisible parasite

Trichinella

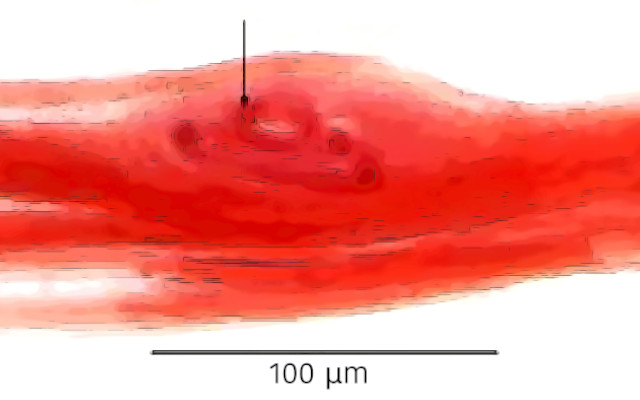

is a roundworm (nematode) that carries out much of its life cycle in some animal species, which, although infested, do not show clinical signs of disease. The parasite becomes embedded in the muscle fibers of carnivorous or omnivorous animals, which become infested by feeding on the flesh of parasitized individuals. Humans become infected mainly by ingesting raw or undercooked meat from suids (pig and wild boar), but the parasite is also found in the muscles of foxes, wolves, raccoons, bears, lynx and mustelids (EFSA, 2011).

T. spiralis

– widespread mainly in pigs and wild boars, rare in other carnivores-is the best known of the four Trichinella species found in Europe, as well as being the most pathogenic species to humans. The species T. nativa occurs mainly in wild carnivores in northern Europe, while T. britovi is widespread in both wild carnivores and suids. Finally, T. pseudospiralis infests both mammals and birds (carnivorous and omnivorous), is widespread in various areas of the old continent but is rare in Italy (Ministry of Health, 2020).

Horse, pork and wild boar meat, cook with care

Several outbreaks of trichinellosis from horse meat consumption were reported between 1975 and 2005 in both France and Italy, the only European countries where horse meat is consumed raw. The horse on closer inspection should not be among the endangered species, as it is a herbivorous animal. Even so, horse meat, particularly from Eastern European animals, has posed a danger to consumers for decades. Probably, according to reports from the National Institute of Health, because they were fed mash containing leftovers from pig slaughter.

Dietary habits therefore strongly affect the spread of human trichinellosis, as consumption of raw horse meat-as well as consumption of raw (fresh sausages, salami) or undercooked pork and wild boar meat-increases the risk of transmission to the consumer.

Trichinellosis, the risks to humans

Larvae embedded in the meat of suidae or equines, following their consumption by humans, are released into the human stomach and pass through the wall of the small intestine, where they develop into adult larvae. The females generate new larvae that, via lymphatic vessels, reach muscle tissues, where they localize giving rise to tissue cysts. After months or years, the cysts may go on to calcification (Gottstein et al., 2009).

Trichinella infestations in humans can be silent if few larvae are ingested. However, in most cases trichinellosis initially manifests with gastrointestinal disorders, fever, and weakness, followed by muscle and joint pain, respiratory distress, and serious complications, such as myocarditis. Periorbital or facial edema and subungual (under the nails) bleeding also occur in some cases. Lethal cases are rare and are related to massive infestations accompanied by clinical complications (Gottstein et al., 2009). Systemic symptoms typically appear 8 to 15 days after ingestion of meat containing Trichinella cysts (EFSA, 2011).

Official public inspections

Trichinella control is mandatory at the European level in slaughter facilities of susceptible animal species, quai pigs and horses. Wild boar meat-which is currently the main vehicle for Trichinella-is also subject to mandatory testing. Regulation (EU) no. 2015/1375 prescribes the sampling and detection of larvae on a muscle portion on all pig, equine and wild boar carcasses. Only pigs raised under controlled housing conditions, certified Trichinella-free, are exempted from systematic inspection at the slaughterhouse, which is therefore performed on 10 percent of the animals instead of all of them.

The ubiquity of controls ensures the detection of parasitized animals. Suffice it to say that in 2018 throughout Europe, no pigs raised under biosecure conditions tested positive, while positivity affected only 0.0002% of pigs from non-Trichinella-free farms. This percentage increases to 0.09% in hunted wild boars and 1.6% in foxes (EFSA and ECDC, 2019). Carcasses of Trichinella-infested animals are declared unfit for human consumption and must be destroyed.

Silvia Bonardi

Bibliography

1) EFSA, European Food Safety Authority (2011). Scientific Report on Technical specifications on harmonized epidemiological indicators for public health hazards to be covered by meat inspection of swine. EFSA Journal 2011; 9(10):2371. [125 pp.] doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2371.

2) EFSA, ECDC(European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control), 2019. The European Union One Health 2018 Zoonoses Report. EFSA Journal 2019;17(12):5926, 276 pp. https://doi. org/10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5926

3) Gottstein B, Pozio E, Nöckler K (2009). Epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control of trichinellosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 22, 127-145. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00026-08. PMID: 19136437; PMCID: PMC2620635

4) Reg. (EU) 2015/1375, laying down specific rules applicable to official controls on the presence of Trichinella in meat. Consolidated text as of 14.10.20 at https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/IT/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02015R1375-20201104

Graduated in Veterinary Medicine and Specialist in Inspection of Food of Animal Origin and in Veterinary Public Health, she is Professor of Inspection and Control of Food of Animal Origin at the University of Parma.