Amazing Amazon. Like a tsunami in a clear sky, the so-called Internet of things (ioT) invades our homes and devours growing market share to physical retailers in an instant. Unpredictable maybe not, underestimated for sure. Already big numbers are dancing, to everyone’s surprise. So what to do, how to deal with the phenomenon? Get on the bandwagon or resist, at what cost and how? Some initial thoughts on the topic.

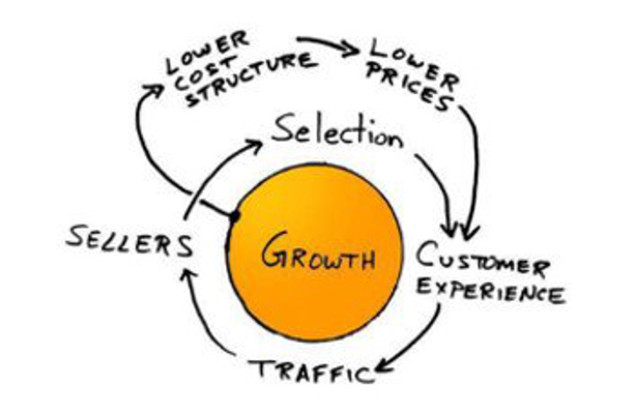

Amazon is not the cause of the crisis of the physical and virtual store. Rather, it expresses the evolution of retail in certain respects. The right giant at the right time-equipped with the best technologies and talent, thanks to huge and continuous investments-grows by double digits even in markets that seemed asphyxiated. Amazon’s consolidated revenues grew between 2004 and 2015 from $6.92 billion to $107.01 billion (to reach $596 million in reported profit, 0.56 percent of revenues). 304 million active customers in 190 countries, 200 million references. The model today is structured on three pillars:

1) Big Data. The egg of Columbus, the most valuable asset of any retail business, is customers and their data. Since 1996, Amazon has already invested in proprietary technologies that enable increasingly accurate profiling of customers transiting its marketplace (304 million unique users, or just under 10 percent of the planet’s Internet web users, estimated at 3.2 billion in 2015). Thus, while ISTAT and trade association study bureaus make estimates on industry trends months late, Amazon analyzes real-time data and updates predictive models based on self-learning AI (Artificial Intelligence) to better target investments and resources.

And what’s more, knowing each person’s ability, frequency and mode of spending, attitudes and tastes enables the advanced algorithm to modulate offers so tailor’s made that the machine rises to the role of the wisest shopping advisor, moreover equipped with an infinite variety of products.

2) Cloud. Amazon is also a leading provider of cloud space. AWS (Amazon Web Services) leases space on its servers to many public and private companies. Its clients include the CIA, Netflix, and most of the world’s start-ups. AWS accounts for 7.9% of the group’s revenues, generating an operating margin of 23% (a very significant share, considering that market place services generate 4% mo).

3) Prime. The Prime club is the equivalent of a loyalty card. An annual subscription (ranging in cost from $7.5 in India to $99 in the U.S., €20 in Italy) that allows, on selected items, to receive very fast delivery (next-day to within hours) without paying for shipping.

The Prime program allows Amazon to increase customer base and loyalty, as well as revenue, by testing privileges and services.

The reverse side of the coin is the higher incidence of shipping costs, which the operator is not always able to pass on to the supplier. And the management of returns, which in turn generates significant costs, albeit transferred to the next accounting period.

Relying on Amazon’s marketplace is the obvious state-of-the-art choice to cover-or supplement-the online sales channel. Because its visibility today is unparalleled, and the costs of setting up and especially maintaining an ecommerce channel are significant. But what are the real costs of Option A?

First, displaying one’s store or product lines on Amazon means giving away customers and their data to the operator, which it can profile, and in fact control, without sharing the value.

The marketplace generates more revenue (commission, up to 25 percent) than it would from direct sales, particularly on low-turnover goods, without dealing with the costs of warehousing and inventory. Meanwhile, when a product reaches levels considered profitable for direct management, Amazon transfers it to its distribution centers. On better terms than those of marketplace merchants, which, however, are not excluded. The same asset may in fact be acquired from different sources (until some succumb, self-eliminating), in the operator’s primary interest of acquiring data (and incidentally, revenue).

In addition, Amazon immediately cashes in on behalf of the third-party store or supplier who is paid at a later stage, net of the commission. Thus it finances its own development at the expense of the suppliers, bringing only the commission into the budget.

To recap, the third-party vendor or store funds Amazon, pays a commission of up to 25 percent plus delivery charges (leaving out fixed costs), and gives away customers and data to Amazon.

Physical retail still has a card to play, the ability to forge a more valuable relationship with the end customer. On a personal, human and social relationship level. Provided we know how to grasp, maintain and enhance it. Not just with points cards, nor with magazine or newsletter subscriptions, but rather with sharing values that transcend the act or repetition of purchases. Examples of success in Italy include the integration of supply chains on territories and their ethicality, the enhancement of local production and factory location, and the removal of palm oil.

However,the excellent initiatives of traditional retail (compared to Amazon) need to be better publicized and shared. Not only in advertising and on their own or affiliated websites, which inevitably tend toward self-referentiality, but also in independent media, and especially on their respective social networks. We need to add narrative, so-called web content marketing, which can stimulate interest and inspire genuine sharing. All the more so in that the physical store experience is not capable of attracting attention, due to its inherent space-time limitations as well as the lack of staff training and motivation with respect to these issues. The consumer must be informed, updated and listened to carefully. Because only transparent and interactive communication ensures the retention of valuable consumers, who may inquire online, but will buy in store.

Physical retail still has an edge, but it must hurry because Amazon-which has also made investments on content, on Washington Post, Amazon Prime Video, and Amazon Studios-will also open real stores, having already tested a bookstore format (yesterday in Seattle, today in NYC) and a grocery store format (AmazonGo). Ecommerce is still worth 8 percent of global trade, and physical retail revenues are therefore its next target.

Amazon is forced to move closer and closer to the end user; it will have to preside over the market in districts where customers with the optimal spending capacity are concentrated. Therefore, the fourth pillar will be distribution centers and physical stores, the opening of which will follow the logic of efficiency, based on numbers and the ability to interpret them, and will, as always, pursue additional and broader goals than they appear. If Nobel laureate Joseph Stiglitz expressed power in terms of information asymmetry back in the day, Big Data management today provides a good example.

Among other things, Amazon finances itself through group companies (AWS) and reinvestment of profits. Its founder Jeff Bezos judges profit redistribution as a missed opportunity for growth. It does not redistribute, and the stock exchange rewards it with more resources.

The investment in AmazonGo is made with internal resources, tested by internal resources (Amazon employees) and external resources (students on college campuses where experimental stores are being opened). Students, talents of today and consumers of the future. Coop’s supermarket of the future after all was built with the help of third-party human resources (Accenture and Carlo Ratti) who, it is given to assume, will try to propose best practices to other retailers.

And after taking additional market share from traditional distribution, Jeff Bezos’ giant will plant the fifth pillar, the shipping pillar. ATS, Amazon Transport Services and FBA, Fulfillment by Amazon will be able to handle their own logistics and outsource many companies’ logistics as well. Which once again will have to carefully weigh the trade-off between focusing on commercial, front office activities and depending on a behemoth that learns and evolves as it works.

What to do?

Globalization has and will bring competitors who do not follow the same rules and have access to superior resources. Resources that they do not only find in the capital market, but know how to seek and create elsewhere. Above all, the big players (Apple, Google, Amazon, Facebook, etc.) invest huge capital in both R&D and the search for talent and ideas. In 2013 Google invested $258 mln in the start-up Uber (moreover, questionable in several respects), while the total investment in all Italian start-ups in the same year bordered on a few tens of millions.

Physical retail can endure only by investing in knowledge and attention to its customers, respect and care for the sensitivities of consumAtors. Proximity and closeness of feeling, sharing appear to be the key resources to preserve retail in the medium/long term.

Technology can offer support, especially in the exchange of information, but it cannot supplant the human relationship that remains the only real competitive advantage available to traditional retail. Keeping in mind that on the other side will soon be Echo (Alexa), the personal assistant that Amazon would like to bring into the homes of all consumers from the second half of 2017, increasing its functionality every day (1).

Italy’s retail trade is different from many other countries. It has not yet been conquered because there are still high barriers to entry for companies like Amazon. Add to that the high use of cash, thanks to which small shopkeepers survive, which is not usable on the digital channel. Amazon knows it, those who control (Internal Revenue Service, Gdf) know it, the capital market knows it. Paradoxically, the unusual (compared to the rest of the world) and extensive use of cash is protecting us. But until when?

Reducing the use of cash is perhaps the time horizon we could give our country to become efficient.

Fighting on an equal footing is impossible; one must be realistic. As much as many jobs will become obsolete and useless, others will evolve: people always make the difference. Because people create Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Facebook. And people need to be able to predict where the road leads or can lead.

An evolution of the ruling class is needed. The ruling class that designed a pension system destined to implode is obviously unable to make proper mathematical calculations. The ruling class that accepts shell companies designed to provide labor to large companies (state and non-state) without paying contributions must be replaced.

A concluding note. Globalization in general terms and the web, ecommerce in particular, have fostered ‘legislative shopping’ phenomena, from worker protection to taxation. With the help of political figures such as Jean-Claude Juncker, Luxembourg’s longtime premier, large groups have disproportionately increased their competitive advantages due to the absence of legislative and fiscal harmonization at the European level.

Applying a Flat Tax to ecommerce businesses, to be calculated based on sales in each geographic area and perhaps redistribute taxes locally seems the easiest tool to introduce to reduce the gap in competitive conditions between local and online retailers.

It would then be possible to control the volume (through data) and quality of the work of companies, Amazon first and foremost, reducing opportunities to exploit different taxation. Britain has done so. As of May 2015, Amazon pays in the UK-and no longer in Luxembourg-tax on sales made in the UK (still in the EU despite Brexit). Waiting for the EU to protect the interests of citizens, workers and local businesses rather than that of large multinational groups.

Dario Dongo and Fabio Ravera

Notes

(1) Echo and Industry 4.0 seem like the future, but they are not accessible to everyone. You have to define which table you want to sit at and which game to play. A grocery store cannot expect to compete with AmazonGo. An RFID tag can cost € 0.10-0.50, a biometric camera system a few tens of thousands. How many €4 sandwiches must a small grocery store sell to amortize the cost of a technology that becomes obsolete in a year, without a tech giant behind it?

Dario Dongo, lawyer and journalist, PhD in international food law, founder of WIISE (FARE - GIFT - Food Times) and Égalité.