II collective mark and the EU certification mark-regulated by the European Union Trademark Regulation (EUTRM, reg. EU 2017/1001)-have a high yet untapped potential, in the agri-food supply chain.

The requirements of novelty, legitimacy and distinctiveness to which trademark law responds also apply to these signs designed to distinguish goods and services that follow shared logic.

1) Collective branding

1.1) Registration

The associations by ‘manufacturers, producers, service providers or traders who, in accordance with the legislation applicable to them, have the capacity, in their own name, to hold rights and obligations of any kind, to enter into contracts or perform other legal acts and to sue, as well as legal persons under public law‘ may apply for registration of an EU collective mark (EUTRM, Art. 74.1. See footnote 1).

Collective marks ‘may serve to designate the geographical origin of goods or services.’ Without, however, authorizing their holders to prohibit third parties from using geographical references in commerce, in accordance with ‘the customs of loyalty in industry or commerce; in particular, such a mark must not be opposed to a third party entitled to use a geographical name‘ (EUTRM, Art. 74.2).

1.2) Regulations of use

Within two months after filing the application for registration, the applicant must file the regulations for use of the collective mark, where the following must be indicated:

– People qualified to use the mark,

– Conditions of membership in the association and, where applicable,

– Conditions for the use of the mark, including penalties.

The regulations for the use of a collective trademark that includes geographical references ‘authorizes persons whose goods or services originate from the geographical area in question to become members of the association that owns the trademark.’ (Art. 74)

2) Certification mark

2.1) Certification and neutrality

The EU certification mark-so designated at the application filing stage-is intended to ‘distinguish goods or services certified by the trademark owner,’ as opposed to non-certified goods and services, in relation to:

– materials,

– Procedures for manufacturing products (or providing services),

– quality, accuracy or other characteristics, ‘withthe exception of geographical origin‘ (EUTRM, Art. 83.1).

Any natural or legal person- ‘including institutions, authorities and public law bodies‘-may apply for an EU certification mark, under a condition of neutrality. That is, the trademark holder may certify the goods and services that other parties use in their respective activities, but must not engage in an activity that involves the supply of the goods or services being certified (EUTRM, Art. 83.2).

2.2) Regulations of use

The application for an EU certification mark must come with its regulations for use within two months after its submission. It should specify:

– The people qualified to use the mark,

– The characteristics that the mark must certify,

– The methods of verifying the characteristics and supervising the use of the mark,

– The conditions of trademark use, including penalties.

3) EU trademarks and national trademarks

The EU trade mark ‘Has a unitary character. It has the same effects throughout the Union: it can be registered, transferred, be the subject of a waiver, a decision to forfeit the holder’s rights, or be null and void, and its use can only be prohibited for the entire Union‘. (EUTMR, Art. 1.2).

EU dir. 2015/2346 – transposed in Italy by d.lgs. 15/2019, amending the Industrial Property Code (Legislative Decree 10.2.05 No. 30) – in turn updated the provisions on national trademarks (2,3). The EU trademark discipline is thus, in effect, repurposed at the level of individual member states. (4)

4) Interim Conclusions

Both EU trademarks, collective mark and certification mark, allow operators to define shared rules for characterizing a product or service and protecting the distinctive sign associated with it. They can also serve as ‘umbrella brands,’ guaranteeing a set of products and services. (5) Also in relation to territories, in the case of the collective mark only. (6)

Reduce the scope of protection of the trademark to a single national territory is undoubtedly cheaper – since registration costs are lower, as are the risks of oppositions involving additional expenses – but it exposes its owner to the risk of ‘brand grabbing‘ which precludes its use in other member countries if others decide to register an even identical mark there.

Dario Dongo

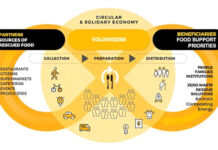

Cover image from Fair World Project, an NGO that promotes organic, fair and inclusive supply chains through third-party certification

Notes

(1) Reg. EU 2017/1001, on the European Union trademark. https://bit.ly/3CCWcwH

(2) EU Dir. 2015/2436, on the approximation of the laws of the member states relating to trade marks. Consolidated text as of 12/23/15 on Europa Lex, https://bit.ly/3N19E1W

(3) Legislative Decree. 20.2.19, n. 15. Implementation of Directive (EU) 2015/2436 to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks and to adapt national legislation to the provisions of Regulation (EU) 2015/2424 amending the Community Trade Mark Regulation. Text updated as of 12/30/21 on Normattiva, https://bit.ly/3Ij73gt

(4) The Industrial Property Code in Italy has moreover assumed the possibility of registering an Italian certification mark also to certify the geographical origin of goods and services (Art. 11-bis, para. 4. See d.lgs. 10.2.05 n. 30, text updated as of 7/30/21 on Normattiva, https://bit.ly/3qeMVWr). However, this rule is contrary to EU rules that prohibit the use of any geographical reference in either the sign, the list of goods and services, or the regulation of use (reg. EU 2017/1001, Art. 83.2). And it is therefore unconstitutional and ineffective

(5) Dario Dongo. Labels and advertising, principles and rules. Il Sole 24 Ore – Edagricole (Bologna, 2004). ISBN 8850651228

(6) Geographical collective marks may also be used ‘in conjunction with the protected designation of origin‘ (PDO) ‘or protected geographical indication‘ (PGI. See EU reg. 1151/2012, Art. 12)

Dario Dongo, lawyer and journalist, PhD in international food law, founder of WIISE (FARE - GIFT - Food Times) and Égalité.