February 10, 2023 marks World Legume Day. These crops are a powerful ally in filling protein needs. Their cultivation has minimal environmental impact, and indeed is a natural fertilizer for the soil.

The cankerworm of protein deficiency

Kwashiorkor is the sad and hard-to-pronounce ailment from which swollen-bellied babies are afflicted, which we remember in photographic accounts of African famines. This is a serious form of protein deficiency that is still widespread in countries where food security is far from assured.

Except in rare cases, people in affluent areas of the planet no longer have any memory of this severe form of malnutrition. Protein deficiency, even in contexts whose average diet has varied margins of questionability (such as the prevalence of junk food), does not in fact exist above a certain level of GDP. Nor (indeed, much less) for those who avoid animal foods.

Protein and plant-based diet

Contrary to a widespread narrative that identifies plant-based diets as a risk factor for protein deficiency, those who eat healthy and varied foods are not in danger in this regard. Whole grains, legumes, oil seeds, and even fruits and vegetables, mushrooms, and algae are sources of protein that we can enjoy on a daily basis.

There is no shortage of side benefits: fresh, organic and whole plant foods are cholesterol-free, rich in fiber, vitamins and antioxidants and keep us safe from obesity.

Within the diverse plant world, legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas, peas, broad beans, chickling peas, soybeans, roveja, mung beans, peanuts, lupins) stand out for their high protein content-referring, of course, to the amount of food we can eat from time to time. In fact, it is unlikely that we get our entire daily requirements from oil seeds.

Legumes and cereals in culinary tradition

There are numerous regional dishes in which they are combined with grains, resulting in tasty, satiating and nutritionally very satisfying preparations. Others include zastoch (pumpkin, potatoes, and beans), risi e bisi (rice and peas), ribollita (wheat and bean bread, pictured on the cover), ciceri e tria (wheat and barley pasta with chickpeas), and crapiata materana (wheat and mixed legumes).

Furthermore, dry pasta made from legume flour is increasingly easy to find commercially and saves us time in preparing additional and innovative high-protein dishes.

There is no need to resort to expensive super-technological solutions that are ethically questionable or foreign to traditional recipes to get your fill of protein. Peasant soups continue to serve us well.

More abundant soup, more efficient food production

As for environmental impact, obtaining the average amount of protein needed for a healthy adult human being (about 60 grams per day) has very different “costs” depending on the source.

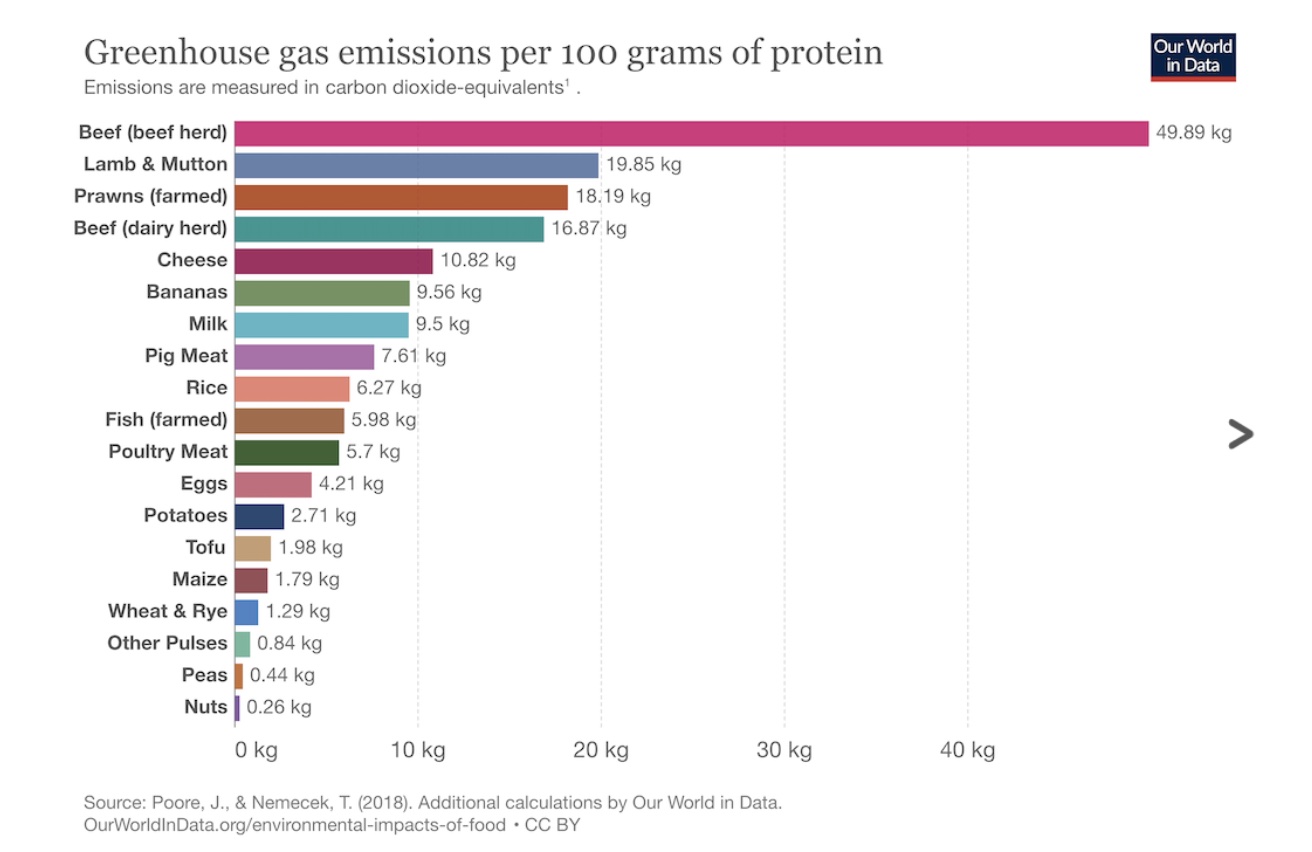

The graphs included below highlight well how legumes (and products made from them, such as tofu) make it possible to eat while minimally impacting the environment. Relative to greenhouse gas emissions.

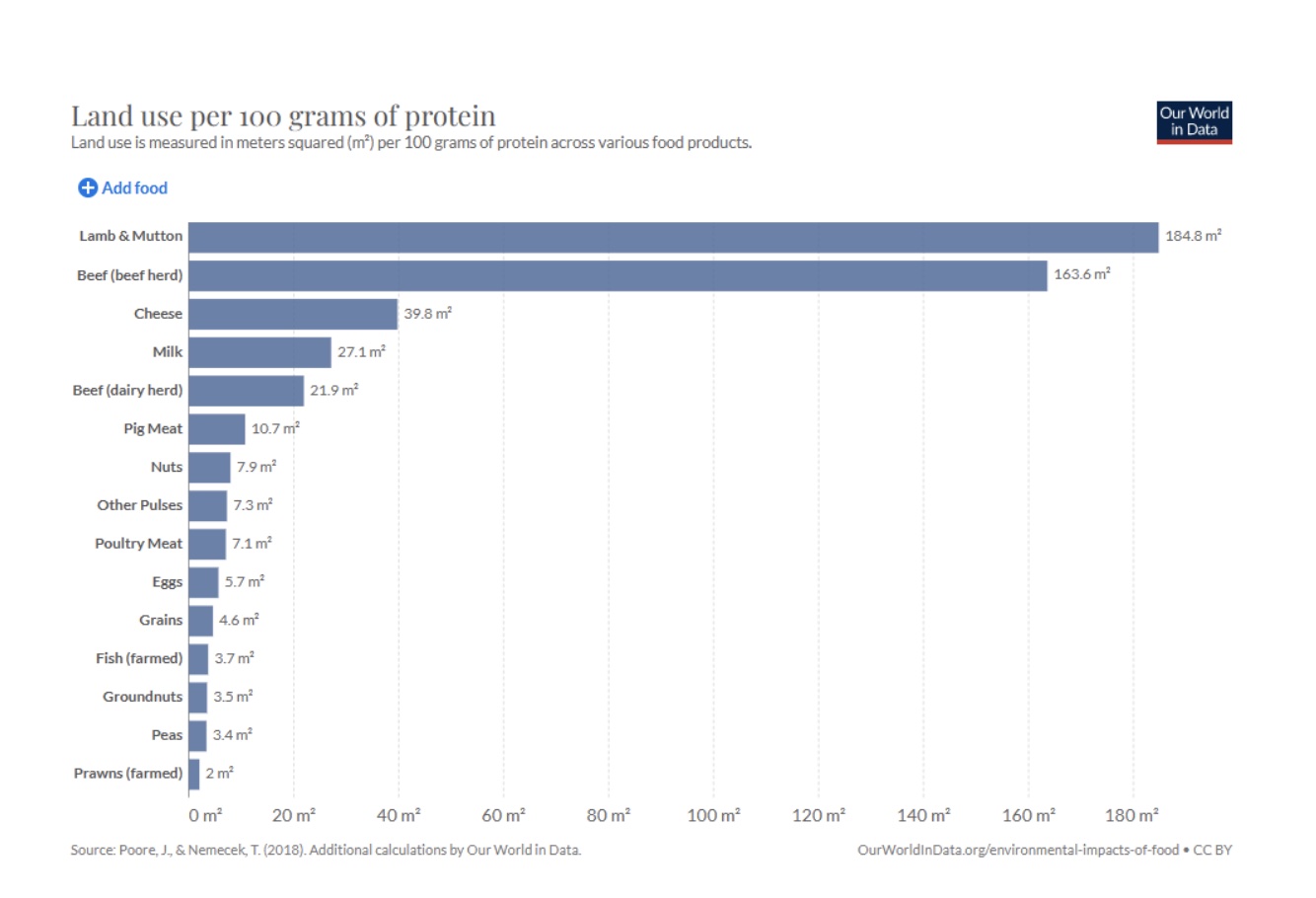

The cost in terms of farmland needed to get the same amount of protein is also very low indeed for beans & company.

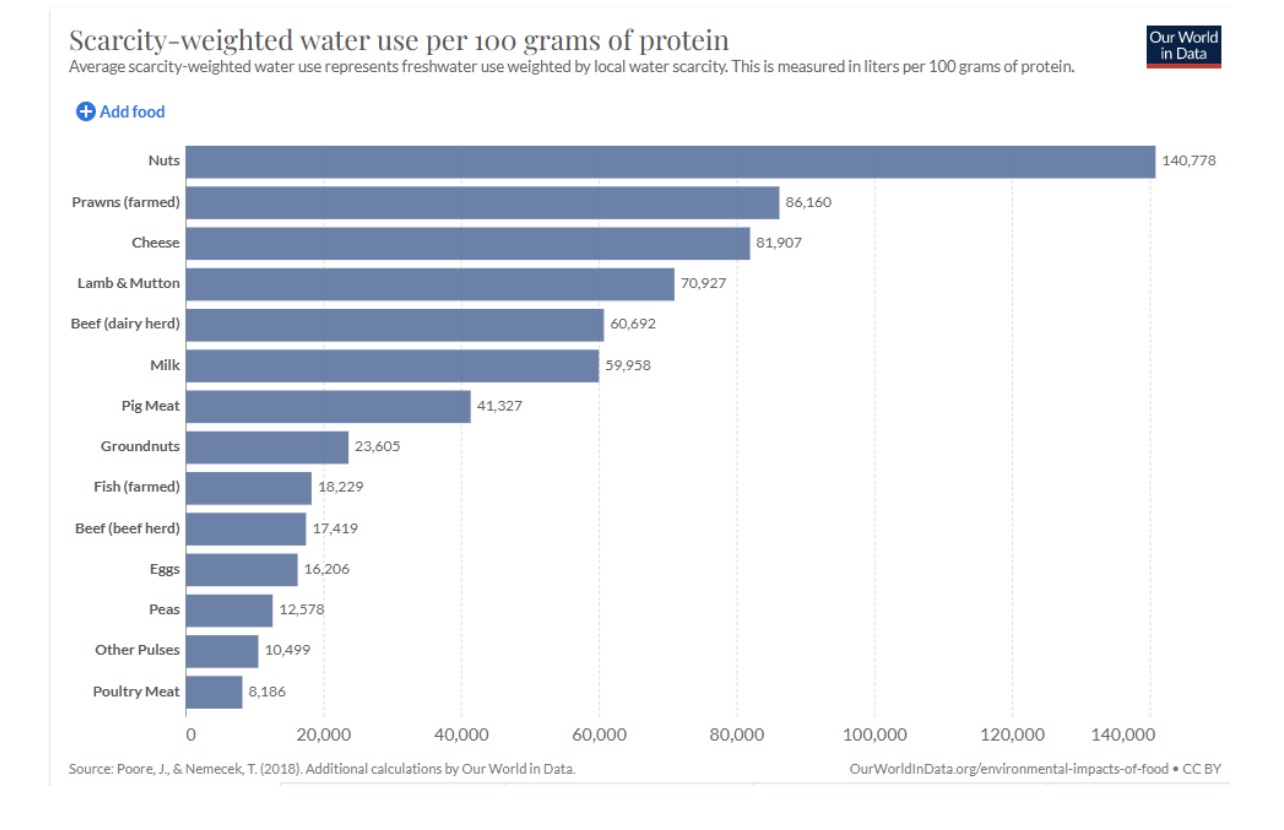

We find the same data regarding the water cost of protein.

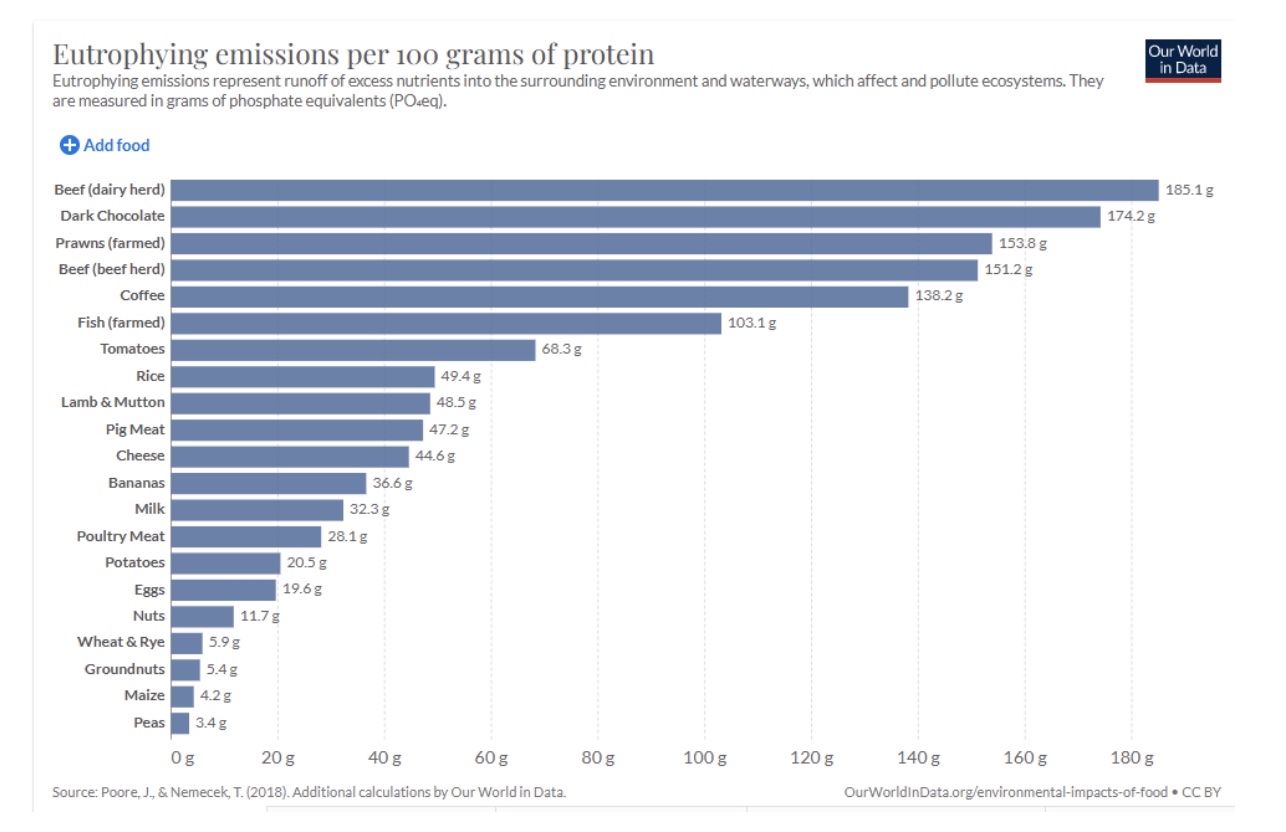

To top it off, the cost in terms of eutrophic discharges (water flows too rich in fertilizers, which initiate processes to destroy aquatic ecosystems) remains consistently low.

By indulging in legumes often and willingly, therefore, you can fully meet protein needs at the lowest possible environmental cost. Choosing such “efficient” foods should be part of the priorities of a conscientious kitchen, in which personal health is not divorced from that of a planet-the only one available to us-inhabited by more than eight billion people, each of whom has a right to proper nutrition.

Friends of the earth and the land

In addition, the cultivation of legumes brings other environmental benefits. The fixation of atmospheric nitrogen, its consequence, allows soils to “recover” from the depletion caused by prolonged grass harvests. In summary, natural fertilization is achieved, allowing for larger subsequent harvests and preventing the overuse of chemical fertilizers.

Dried legumes, moreover, are in themselves an anti-waste food category, since they do not rot and can remain in the pantry for a long time.

Considering that a significant portion of food waste can be attributed to the problematic nature of post-harvest storage and maintaining the cold chain, legumes again appear to us to be lifesaving.

World Legume Day 2023 falls in the International Year of Millet, convened by FAO to promote the cultivation and consumption of a drought-resistant cereal, rich in valuable nutrients, and suitable for cultivation on marginal lands. These are all characteristics in common with legumes, of which “alternative” grains (to wheat, rice and corn) are, therefore, natural allies.

Returning to our own territory, Italy is fortunate to take advantage of many local varieties to be rediscovered. Among the many – and delicious – examples are the dwarf pea from Zollino, the black chickpea from the Murgia Carsica, the aforementioned roveja from Civita di Cascia, the lentil from Castelluccio, and the Tuscan zolfino bean.

The rediscovery of legumes

Since the 1960s, land devoted to growing legumes has declined dramatically-coinciding with the decline in consumption-but recent years have been the protagonists of an interesting reversal of the trend, albeit insufficient to meet domestic needs.

These results would probably not have been achieved without the valuable cultural work of associations such as Slow Food, whose rediscovery of regional varieties and traditional agricultural practices can provide new food insights to diverse audiences, even those far removed from environmental concerns.

It seems, therefore, incumbent on us to go in search of local organic productions, which make it possible to sustain virtuous agricultural realities, stop the depopulation of inland areas and, in the long run, allow a “return to the poor origins” of regional cuisine. This time, from an ecological, health-conscious and ethical perspective.

Roberta Seclì

Professional journalist since January 1995, he has worked for newspapers (Il Messaggero, Paese Sera, La Stampa) and periodicals (NumeroUno, Il Salvagente). She is the author of journalistic surveys on food, she has published the book "Reading labels to know what we eat".