‘Novel foods’ simultaneously express a market opportunity for innovative products and the opportunity for consumers to access a wider variety of foods capable of contributing to nutritional and health needs.

Below is the state of the art on novel foods in the European Union. Responsibilities of operators, procedures, ongoing evaluations by EFSA (European Food Safety Authority), authorizations by the European Commission.

1) ‘Novel foods’, the European concept

Novel foods Regulation (EU) No 2015/2283 identifies foods as ‘novel foods’ those of which:

– lacks (evidence of) ‘significant’ experience of consumption in the European Union (including England. See paragraph 7, subparagraph below) before 15 May 1997, and

– belong to one or more of the following categories:

i) foods with a ‘new or deliberately modified molecular structure‘ not used for human consumption in the EU before 15.5.1997,

ii) foods consisting of, isolated or produced from microorganisms, mushrooms, seaweed (o microalgae),

iii) foods consisting of, isolated or produced from materials of mineral origin,

iv) foods consisting of, isolated or produced from plants or their parts. Except those which have a history of safe use as food in the EU and are made up, isolated or produced from a plant or variety of the same species obtained by:

– traditional breeding practices used for food production in the EU before 15.5.97, or

– non-traditional breeding practices, not used for food production in the EU before 15.5.97, provided that they do not lead to significant changes in the composition or structure of the food such as to affect its nutritional value, metabolism or content of undesirable substances ,

v) foods consisting of, isolated or obtained from animals or parts thereof, therein including insects. Without prejudice to products with a history of safe use as food in the EU, prior to 15.5.97, from animals obtained through traditional breeding practices,

vi) foods consisting of, isolated or produced from cell cultures o of tissues that derive from animals, plants, microorganisms, fungi or algae,

vii) foods resulting from a ‘new production process‘ not used for food production in the EU before 15.5.97 ‘ which involves significant changes in the composition or structure of the food which affect its nutritional value, metabolism or the content of undesirable substances’

viii) foods consisting of ‘engineered nanomaterials’,

ix) vitamins, minerals and other substances, used in accordance with Food Supplements Directive 2002/46/EC, Addition of Nutrients Regulation (EC) No 1925/2006, Food for specific groups Regulation (EU) No 609/2013, which:

– result from an innovative production process (not used in food production in the EU before 15.5.97), or

– contain (or consist of) engineered nanomaterials,

x) foods (and their ingredients) used exclusively in food supplements, before 15.5.97 in the EU, if intended for use in foods other than ‘food supplements’. (Novel Foods Regulation EU No 2283/2015, article 3.2).

2) Responsibilities of operators, importers and retailers in the European Union

The operators of the food sector and food importers in the European Union are primarily responsible for verifying the status – traditional food or ‘novel food’ (a notion that includes traditional foods from third countries) – of the products they produce or import. To their responsibility is added that of retailer who, please note, are responsible for ensuring the conformity of the products they distribute with the applicable legislation.

3) Consultation procedure

In the event of uncertainty on the status of a food, the operator can activate a consultation procedure with the competent authority in the Member State where he intends to place the food on the market for the first time. This procedure:

– must be carried out before placing the product on the market, in order to prevent disputes and sanctions in administrative and judicial settings if the food is finally recognized as a ‘novel food’ (as has recently happened, following the ruling of the ‘Court of Justice of the European Union’, in the case of buckwheat rich in spermidine),

– does not guarantee a homogeneous interpretation of EU rules and entails the real risk of altering competition between companies operating in different member countries, as well as hindering the free movement of goods, depending on the greater or lesser propensity of their governments and authorities towards food innovation. It is therefore necessary to centralize the consultation procedure, in the awaited reform of the Novel Foods Regulation (EU) No 2283/2015.

4) Authorization procedure for ‘novel foods’ in the EU

The authorization procedure – which in the first Novel Foods Regulation (EC) No 258/1997 provided for an investigation phase in the individual Member States, as still happens for the consultation procedure (see previous paragraph 3) – has already been centralised, thanks to the reform that took place with the current Novel Foods Regulation (EU) No 2283/2015.

Placing on the EU market of foods and food ingredients classified as ‘novel food’ (see paragraph 1 above) must be preceded by the green light from the European Commission. To this end, the interested operators – any natural and/or legal person, even in groups (i.e. research consortia, temporary business consortia, sector associations) can resort to two procedures:

– ordinary authorization, to be proposed by completing a specific dossier to be attached to the application addressed to the European Commission. The applicant can request ‘data protection’ which, if granted, translates into exclusivity on the marketing of the new food for 5 years,

– notification of the intention to place a traditional food from a third country on the EU market. A simplified procedure, as we have seen, which in any case requires the collection of solid proof of safe consumption of the product for over 25 years. (2) Without the possibility of exclusivity based on ‘data protection’, unless resorting to the authorization procedure.

5) Scientific evaluation by EFSA

EFSA, the European Food Safety Authority, receives from the Commission applications for authorization of ‘novel foods’ and notification of traditional foods from third countries, on the safety of which it is called upon to express a scientific opinion. The Open EFSA website allows you to consult the status of the risk assessments entrusted to the Authority. (3)

The ‘novel foods’ item, in the ‘food domain’, currently refers to 273 dossiers divided as follows:

– nature of the dossier. 268 dossiers concern applications submitted by FBOs (food business operators), another 5 relate to internal scientific opinions (i.e. guidelines, CBD safety statement),

– type of procedure. 252 requests for authorization of novel food, 1 request for authorization of a traditional food from a third country, 15 notifications of traditional foods from third countries (15),

– status of the procedure. 70 opinions published, 5 in the process of being published. 96 ongoing risk assessments, 64 still to be started. 22 invalid requests, 16 withdrawn requests,

– Transparency Regulation (EU) No 1381/2019. 187 applications were submitted before the entry into force of the TR (27 March 2021), 86 after.

6) Decision of the European Commission

The European Commission can decide to authorize ‘novel food’ or not – under the conditions proposed by the applicant, who can also agree to their variation – regardless of the positive or negative outcome of the EFSA food safety assessment:

– authorizations are granted through specific implementing regulations of the Commission, published in the Journal which modify the ‘Union list of novel foods’ official. (4)

– refusal decisions can be consulted (in part) on the appropriate register of documents (5,6).

Log analysis of the Commission’s decisions and the dossiers in Open EFSA allows us to observe how the majority of applications were rejected due to simple non-compliance with the Transparency Regulation (EU) No 1381/2019 (i.e. lack of or delay in the notification of the scientific studies supporting the application) and, only in a few cases, due to a lack of data available to EFSA for risk assessment purposes.

7) Verification of the ‘novel food’ status and any authorizations

Authorized ‘novel foods’ in the European Union – together with their conditions of use and information to the consumer – are listed in the list defined by Reg. (EU) 2017/2470. (4) Other information may be collected on:

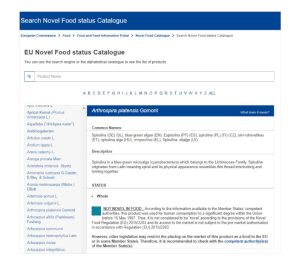

– ‘EU Novel Food status Catalogue’, a non-exhaustive list of the status of some foods, based on assessments by the European Commission which have no legal value, (7)

– ‘Consultation process on novel food status,’, containing the results of the consultations requested so far from the Member States, (8)

– ‘Summary of applications and notifications’. A summary list of novel food applications and notifications submitted to date in the EU. (9)

DG Sanco (now DG Sante), under the validity of the first Novel Foods Regulation (EC) No 258/1997, had published a guidance document on the criterion of ‘Human Consumption to a Significant Degree’. (10) The consultation procedure now offers further support, although its outcomes do not guarantee uniformity of interpretation at European level (see paragraph 3 above).

8) Critical issues and areas for improvement

Opportunities offered by research and innovation on new foods – and the possibility of introducing into the Old Continent valuable foods that belong to the traditions of third countries (e.g. chia seeds) still encounter a series of obstacles linked to:

– complexity of the procedures, antithetical to the GRAS (Generally Accepted as Safe) approach which on the other hand does not appear to have so far caused food safety problems in the countries where it has been applied for decades (e.g. USA, Canada),

– delays, even significant, in the management of authorization dossiers by EFSA and the European Commission. These delays can be attributed both to the complexity of the procedures and to the lack of staff and resources in EFSA (whose budgets are approved every year by the European Parliament),

– grants of authorizations with five-year exclusivity not justified by patents, as well as in conflict with various international regulations. (11) To the detriment of free competition between operators as well as the availability and accessibility of potentially beneficial foods to large sections of the population,

The number of applications for authorization of ‘novel foods’ and notifications of traditional foods from third countries, a few dozen dossiers every year, in a market now made up of 27 member countries, cannot on the other hand justify the months and years of delay in ‘time-to-market’ of new foods.

9) Provisional conclusions

The innovation in the food sector it is preached in every European strategy and programme, with a variety of objectives relating to sustainable development (reduction of the ecological footprint of production, circular economy, ‘upcycling’) to ‘food security’ and ‘nutrition security’, without neglect the competitiveness of the leading manufacturing sector in the EU.

The discipline ‘novel food’ has been introduced a quarter of a century ago but its application represents the bottleneck between research, innovation and its concrete application, to the benefit of the economy and society. The European Union is still referred to as the first global food trading platform but risks losing this primacy due to ‘over-regulation’ and bureaucracy.

Dario Dongo and Andrea Adelmo Della Penna

Footnotes

(1) Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 on novel foods, amending Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 and repealing Regulation (EC) No 258/97 and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1852/2001. Consolidated text 27.3.21 https://tinyurl.com/rfkzmwxx

(2) A traditional third country food is a food that has a history of safe use as a food in a non-EU country. This definition includes only foods consisting of, isolated or produced by microorganisms, fungi, algae (including microalgae), plants or their parts, animals, or their cell cultures, which fall within the definition of novel food

(3) Open EFSA https://open.efsa.europa.eu

(4) Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2017/2470, establishing the Union list of novel foods in accordance with Regulation (EU) 2015/2283. Latest consolidated version 22.8.23 https://tinyurl.com/yyz2vs3d

(5) European Commission. Transparency Register. Request a Commission document https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/documents-request/search

(6) The complete list of decisions, without the possibility of access to documents, is available in the section dedicated to ‘novel foods’ on the website of the European Commission, DG Sante https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/novel-food/decisions-terminating-procedure_en

(7) EU Novel Food status Catalogue https://ec.europa.eu/food/food-feed-portal/screen/novel-food-catalogue/search

(8) Consultation process on novel food status https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/novel-food/consultation-process-novel-food-status_en

(9) Summary of applications and notifications https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/novel-food/authorisations/summary-applications-and-notifications_en

(10) European Commission, DG Sante. «Human Consumption to a Significant Degree». Information and Guidance Document https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2016-10/novel-food_guidance_human-consumption_en.pdf

(11) Dario Dongo. ‘Novel food’ with exclusivity and market distortions. GIFT (Great Italian Food Trade). 29.10.23